In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

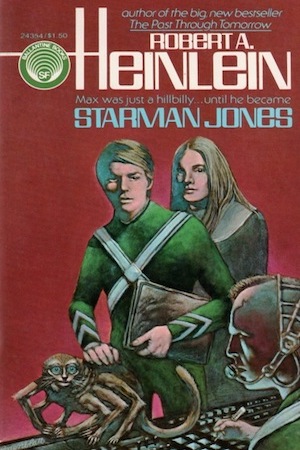

As Robert Heinlein’s juvenile series progressed, the tales took place further and further from Earth. And with Starman Jones, the series left the Solar System entirely, following the adventures of young Max Jones, a gifted young man who wants nothing more than to emulate his space-faring uncle and venture out into the galaxy. Along the way, he makes friends, breaks rules, learns new skills, and has adventures enough to last a lifetime.

Heinlein always did something different with each juvenile. In Starman Jones, more clearly than any other book in the series, the tale explores the difference between laws and regulations on one hand and morality on the other, and examines how those who break the law can also be in the right. My first exposure to Starman Jones was a library copy, which I believe I read in my twenties. By that age, I was used to stories where the lines between right and wrong were blurred. I wonder what my reaction would have been if I had read it in my early teens, like some of the other Heinlein juveniles.

For this review, I used a paperback copy borrowed from my son, and then found the book included in a Science Fiction Book Club omnibus edition entitled To the Stars.

About the Author

Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988) was one of America’s most widely revered science fiction authors, frequently referred to as the Dean of Science Fiction. I have often reviewed his work in this column, including Starship Troopers, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, “Destination Moon” (contained in the collection Three Times Infinity), and The Pursuit of the Pankera/The Number of the Beast, and Glory Road. From 1947 to 1958, he also wrote a series of a dozen juvenile novels for Charles Scribner’s Sons, a firm whose children’s divisions was interested in publishing science fiction novels targeted at young boys. These novels include a wide variety of tales, and contain some of Heinlein’s best work (Note: I’ve linked to the reviews of books I’ve already discussed in this column): Rocket Ship Galileo, Space Cadet, Red Planet, Farmer in the Sky, Between Planets, The Rolling Stones, Starman Jones, The Star Beast, Tunnel in the Sky, Time for the Stars, Citizen of the Galaxy, and Have Spacesuit Will Travel. This is not the first time Starman Jones has been discussed on Tor.com, as Jo Walton reviewed it over a decade ago.

Predictions Gone Right and Predictions Gone Wrong

Looking at older science fiction stories, especially ones like Starman Jones written over seven decades ago, it is always interesting to see what predictions the authors got right, and which fell short. The prediction or assumption that ship’s crews would always be exclusively male, for example, turned out to be wrong even before the end of the 20th century.

In Starman Jones, young Max has a tough life on the family farm in the Ozarks. There is a maglev train that passes nearby, but it is for the more fortunate, not folks like Max. When Max leaves home, he does so on foot, planning to sleep anywhere he can. Like all who lived through the Great Depression, Heinlein had seen a lot of poverty, and viewed economic inequality as something that would continue into the future. That prediction has held up well over the subsequent decades, and looks like it will continue long into the future. As far back as the New Testament, written nearly 20 centuries ago, Jesus tells his followers that the poor will be with us always, and it sadly appears that betting against that statement will always be a losing proposition.

One place where Heinlein saw the future a little less clearly is in the field of navigation, or “astrogation,” as he calls it. Those scenes were very evocative to me, reminding me of my own days in the 1970s as a deck watch officer on a Coast Guard cutter (and for a short time at the end of my tour, as the navigator myself). The Coast Guard had taken Loran A radionavigation stations offline, but was having problems getting newer Loran C units to work on our class of vessels, so when we were out of radar range of land, we did things the old-fashioned way. The astrogation tables that Max has memorized bear no small resemblance to Publication 229, the Sight Reduction Tables for Marine Navigation, which I used with a chronometer, sextant, charts, and other resources to plot my vessel’s position. But the days of old-fashioned navigation were ending. A new ensign reported to the cutter, having been issued a programmable calculator that seemed to be able to spit out pretty much all the numbers from the tables in Pub 229. And Loran C was soon supplanted by yet another system, and mariners had satellite-based GPS to draw upon. The last time I was on the bridge of a cutter, their position was fixed by computer and displayed on a TV screen without need for any human navigator at all, making me feel like an expert in something as archaic as producing buggy whips. Heinlein predicted travel to other stars, but didn’t anticipate the impact that advanced computing devices could have on guiding that travel.

Another computer innovation Heinlein didn’t see coming was the centralized database. The fake credentials that Max and Sam used to gain a berth on a star liner would not have survived modern scrutiny, and cross-checking with electronic records. For better or worse, there is much less opportunity for someone in modern society to put their old life behind them and start anew.

And those fake credentials bring up another topic, more based on sociology than technology. When I went to sea, sailors could be a rough lot. They worked hard, but they also got into trouble, and competence was valued over conformance to regulations. One of the best petty officers on my ship had made second-class petty officer three or four times, losing that rank again and again because of disciplinary infractions, but regaining it because of his skills and abilities. In subsequent decades, with the best of intentions, there arose an emphasis on “zero tolerance” for disciplinary actions, and for officers in particular, any hint of negativity in a fitness report could end a career. The days of the capable rogue were ending, and conformity became the watchword. I hope that is not a lasting trend, and that the pendulum will eventually swing back the other way. I would rather serve with someone competent, even if they are rough around the edges, than someone who presents themselves well and looks good on paper. The character Sam in Starman Jones might not be someone I would trust with my wallet, but I would trust him with my life.

Starman Jones

As mentioned above, we’re introduced to Max Jones while he’s working on the family farm. About the only possessions Max has are a claim to the farm (controlled after his father’s death by his unreliable stepmother), and a set of interstellar navigation tables left to him by his late uncle. When a new stepfather enters the picture and it looks like the land will be sold off, Max hits the road on foot to the nearest spaceport, hoping his uncle left word that he should be admitted to the hereditary astrogators guild. Max is blessed with an eidetic memory, which we see him use to calculate the time by the position of the stars, and also to recall train schedules, so he can cut through the maglev train tunnel to save time. His calculations are a bit off, however, and he is almost squished into a pulp by the shockwave of a passing train as he leaves the tunnel. Max has also memorized those books of astrogation tables, a skill that will be vital later in the story.

Max meets a hobo named Sam, who shares his dinner. Sam coaxes Max’s story out of him, and Max admits that if his uncle, who was childless, registered Max with the astrogator’s guild, he might be able to join. They go to sleep, and Max awakens to find Sam gone, along with the astrogation tables, which are worth money if turned back into the guild. Max continues on and reports to the guild hall, to find that Sam, impersonating him, had attempted to turn in the tables, but was rebuffed. They sadly inform Max that his uncle left no instructions for him, but pay him the bounty for returning the tables.

Max then encounters Sam again, and is convinced to spend his bounty on fake identification papers for the stewards guild that will get them a berth on the space liner Asgard, and off into space. Sam tells Max the story of a man he knew, an Imperial Marine named Roberts or Richards, who missed a ship’s movement, did not want to face the consequences, and kept putting off surrendering himself to the authorities. While Sam denies it, Max suspects he was that Marine (the idea that humanity is now organized into an empire is intriguing, but Heinlein doesn’t waste time explaining that further).

Max doesn’t enjoy the work of a steward, but does his best at menial tasks like caring for the pets of the rich passengers. One of these is a spider puppy named Mr. Chips, owned by a young woman named Eldreth. She takes a liking to Max, and soon has wrangled permission from his boss for him to play three-dimensional chess with her. She turns out to be quite a well-connected passenger, is impressed by his knowledge and math skills, and advocates for him with the ship’s officers. The next thing Max knows, he is being allowed to strike for a position as junior chartsman, working alongside the astrogators.

The Chief Astrogator, Doctor Hendrix, is a kindly man, and served with Max’s uncle. But one of the junior astrogators, a sour man named Simes, is not very competent and jealous of anyone who might compete with him. We get a lot of descriptions of astrogation procedures which, despite the outdated technology, feel very true to what happens on the bridge of a ship. Max does well enough that he is designated as a merchant cadet, which allows him to dine with passengers, including his friend Eldreth. Meanwhile, while he proves himself an able leader, Sam can’t avoid the temptation to get involved in some irregular activities, and get busted down to swabbing decks.

Soon the death of Doctor Hendrix upsets the smooth operation of the astrogation department, and in a critical maneuver, the Captain makes an error that sends the Asgard to unknown regions, where it appears likely they will be trapped forever. They find a habitable planet, but order and discipline begin to break down as people realize they might never get home. The Captain has a nervous breakdown, and before long, is dead. And when the planet turns out to be inhabited by mysterious and malevolent aliens, their situation looks even bleaker. Soon, Max and Eldreth are captured by the aliens, and taken to meet their fate—which might even involve ending up in a cookpot. But the little spider puppy Mr. Chips knows where they are, and Sam soon heads out to the rescue. It turns out they have one last hope for leaving the planet…and it requires Max, and his perfect memory, to get back to the ship.

The book has a wonderfully bittersweet ending, a very fitting conclusion to one of Heinlein’s better juveniles. Max, despite his incredible mathematics abilities, feels very real and grounded. And Eldreth, despite being present in the tale as the obligatory love interest, is a strong character in her own right. But it is Sam, equally gifted and flawed, who steals the limelight every time he is mentioned, becoming one of my favorites of all Heinlein’s characters.

Final Thoughts

Starman Jones is an enjoyable volume in Heinlein’s series of juveniles, definitely ranking near the top of the list. There is lots of action and adventure, plenty of jeopardy, engaging characters, and interesting moral dilemmas.

And now it is time for you to talk and me to listen: What did you think of Starman Jones? How do you think it stacks up against Heinlein’s other juveniles? And as a fan of stories involving navigators managing faster-than-light travel, I’d enjoy hearing about other such stories you may have encountered.

After the obvious[1], this may be my favorite Heinlein; it is certainly my next favorite of his juveniles. And the Tor.com staff have picked the cover of my paperback, from back in the day.

I renewed to step up the pace on my current Big Read so I can do the Heinlein Big Read I want to do before I croak.

[1] I can’t say what that is because the forum software won’t allow links in posts any more.

Typo, I think.

I read this one, appropriately, when I was a juvenile myself. All I really remember about it are Max’s narrow escape on his trip to the Guild Hall, and the passage on the bridge where the ship gets lost. Also, Max’s surprise when some of the upper-crust passengers knuckle down and apply themselves to setting up their impromptu colony. Good to hear that Heinlein got the feel of astrogation right, but not surprising – he had a naval background, didn’t he?

I enjoy these short visits to books from the past, Alan, and hope that there are many more to come.

@2 – Fixed, thanks.

IIRC, his calculations were fine but he didn’t allow for the possibility of a special unscheduled train. (I guess that could be considered to be “his calculations are a bit off”, but as that’s something he couldn’t have calculated no matter how much knowledge he had, I would put it as “he calculated correctly but almost got extremely unlucky”.)

This has always been my favorite of Heinlein’s juveniles—I’ve always been a sucker for people with unbelievable talents (cf. “Slipstick” Libby). Thanks for the trip down memory lane.

One of my favorites growing up — I read it first in hardback at the library, with illustrations, and still own the Dell paperback. I still like the explanation of wormholes, and the difficulty of astrogating when all of your reference points are moving. Not to mention adjusting for speed-of-light delays, and I don’t recall Heinlein mentioning that.

An interesting counterpart is Marion Zimmer Bradley’s 1963 The Colors of Space, also the story of a young man who uses fake documents and cosmetic surgery to get a berth on an interstellar ship.

Heinlein had a hang-up about unions, though; given when he came of age, his constant use of “guild” – and in terms more congruent with the Medieval or early Modern era in Europe – rather than simply “union” and something more congruent with the SIU, SUP, AMO, etc., much less the ALPA.

Kind of illuminating that despite his personality – and being a 4F in WW II – he was always (as witness the bit in Starship Troopers) sniping at professional mariners and aviators who had spent more time at sea, in the air, and under fire, than he ever did …

Mr. Heinlein was not the only sf writer of the 1950s and ’60s who missed the computer revolution. Dr. Asimov used to point out that right up to the actual Moon landing, sf stories regularly featured complex math/engineering calculations being done by hand (with slide rules!). And communications were regularly via radio, no time for the new-fangled tee-vee stuff!

This is one of my favorite Heinlein juveniles, I think mostly because it’s more about what Max learns about people than about any of the math/astrogation stuff — although it’s well done, however outdated it is. And you’re right, Sam is a great character.

This wasn’t one of the ones that Dad owned (and which I subsequently appropriated), but I managed to lay hands on a copy at one point or another (the same Ballantine paperback shown above). It’s not quite my favorite of the juvies, but it’s certainly very high on the list.

The most important line in Starman Jones comes from Samuels, the Purser. “A ship,” he says, “is not just steel. It is a delicate political entity.”

Heinlein may get the steel wrong, along with the astrogation tables and the computer technology, but none of this really matters, because he gets the social structure of the ship so very right.

Jones is one of Heinlein’s most sophisticated novels, second only to Citizen of the Galaxy. It is about authority and responsibility, and about the ways they can be delegated, but never avoided. It is about the discipline of Crew Resource Management, although it been invented at the time Heinlein was writing. (Now there’s a prediction for you;-))

Hendrix is massively competent, but he takes on the full burden of astrogation himself, refusing to share it effectively, and the strain kills him. That is his tragic flaw

Symes is good enough to know that he is not quite good enough, but is unable to seek help, or find a way out. That is his tragic flaw.

And Captain Blaine, who takes over after Hendrix’s death, knows that he must delegate, but does not know his crew well enough to know who he can delegate to. There is his tragic flaw, and it is by far the worst, because he alone is responsible for ensuring that his crew can do the job.

It is left to Max to recover the situation. To a large extent he takes the burden upon himself, because he has no other choice. But he has already set himself up (perhaps unwittingly) with a crew that supports and trusts him, because he has demonstrated the essential qualities of a true captain.

I have heard, but cannot verify, that Heinlein himself did predict that, but had a story involving pocket calculators turned down by an editor as excessively implausible, so he kept such devices out of his stories thereafter.

The problem with competent rogues is where they go rogue. If it’s being a creative supply officer that’s fine, if it’s deciding that the best way to deal with the VC near the village of My Lai is killing every possible VC in the village you’ve got a problem. It’s hard to detect the latter in peacetime, except that they do tend to do what they can to make their lives easier everywhere.

It’s been over 50 years ago that I read “Starman Jones” so many of the details have turned fuzzy. I do recall that this novel introduced to me the concept of “eidetic” memory. I’m still uncertain if this can be an acquired trait or if it must be congenital but I was always envious of those that had it. That skill along with “photographic” memory, which is something else entirely, set me on a path of investigation into how these two abilities can influence overall IQ. My research continues but the indications are that memory, recall, and synthesis are three pillars of a highly advanced mind and are present in many of the geniuses throughout history. The character of Jones in this story seems to illustrate the point that superior mental capabilities alone do not always result in a socially competent individual. Whether or not Heinlein intended to make this point ends up being irrelevant since this is what I obtained from it. This would prove to be the case also with many of Heinlein’s other works. I have never read anything by the author that didn’t satisfy my hunger for entertainment.

A nice review, for one of Heinlein’s better juveniles.

The description of Sam, who steals every scene he is in – and not just with his delightfully incongruous double cliches – reminds me that it’s not the only time Heinlein does this. One could say the same about Dak Broadbent, who is a supporting character in Double Star but steals every scene he is in… and who, like Sam, is a loveable rogue who bends the rules but does the right thing.

A fun read. I always felt like he killed the romance at the end for Boy’s Life, or whatever mag he was writing for at the time. Sex was never really even discussed. I thought the social structure of the ship felt real to life and the characters except RAH had a bit of an issue with bad guys like Symes. I think the reason the juveniles work so well is he writes naive very well and kids could relate. I read this back in the 60s when I was at or close to being a teen. I still have a copy of pretty much anything Heinlein ever wrote

…he died in approved Marine style. Loved that line as a teen still love it in my 60s. Great book, one of my favorites.

I don’t believe science fiction writers missed electronic computers; I think they went to a lot of trouble to write them out of the picture because they hadn’t yet figured out how to write adventures without excluding them. Larry Niven had his interstellar faster than light ships piloted using the psychic powers of organic brains, to rule out computer piloting, and Frank Herbert had a historical revolution centred around the wholesale rejection of electronic calculators.

Too bad they couldn’t have come up with a better cover. Looks amateurish.

This book was my gateway into scifi literature when I was 10.

@@.-@ Thanks for pointing out the line about the special train. The way I had read it cut against the points Heinlein was making about Max’s memory and math abilities.

@10 That “a ship is not just steel” quote is a great one. Another thing I noticed about this book is thinking through the impact of jetless propulsion on shipboard life. Unlike earlier juveniles, this one did not show ships with tiny crews, and an obsessive focus on cargo mass. Instead, Asgard had a crew similar in size to a current ocean liner.

@12 The competent rogues I was talking about had a disregard for regulations, but not for morality. Killing noncombatants does not make you a rogue, it makes you a war criminal.

@16 That line about the manual-approved form is great, but has become an anachronism. Steadying your pistol with your left forearm is generally a thing of the past.

First two SF novels I ever read were Heinlein’s Starman Jones, with the original Clifford Geary illos, and Andre Norton’s The Stars Are Ours (wasn’t entirely new to SF; had Dan Dare and the odd BBC serial to inflame my fevered young brain). Both blew the doors off my ten-year-old mind. Just off the ship, my first library card, and a good stock of RAH and Norton juveniles—holy cow, was I set!

Agreed, his juveniles have some of his best work. Always have an ironic chuckle to reflect that RAH, the Great Libertarian, did his best work when tightly edited, but he double-dog hated being edited by anyone not named John W. Campbell Jr. But if it hadn’t been for her stern refusal to indulge his more egotistical desires by ‘that Dalgleish woman’, these wonderful novels almost certainly would not have been as good.

I was surprised to discover that—trying hard here not to introduce a spoiler—RAH’s plot-use of chain-of-command was based on a real incident during the War of 1812 in the naval battles on the Great Lakes, though with a far less happy outcome for the officer involved.

@20 Indeed, Starman Jones is clearly set on an ocean liner in space ;-) One of Heinlein’s skills was the ability to extract the essential details of something he had seen or experienced, and use those to build up the new worlds he was inventing. I think this combination of flights of fancy, grounded in reality, is what makes his work still readable, even if it’s superficially dated.

“He Ate What Was Set Before Him”

@20, also, thinking about it some more, I’m not sure “competent rogue” is quite the right term for Sam. At the very least, there’s more to it than that.

Heinlein’s treatment of rules and authority is complex. He has an anti-authoritarian streak to him, but he also understands the importance of order and discipline. His worldview seems to be that there are both written and unwritten rules, and many of his characters spend their time deciding which of the written rules they can break in order to keep to the unwritten ones.

Starman Jones is full of unwritten rules. When Max becomes an officer, he soon realises (through the subtle guidance of other crew members) that his social status has changed. He can now do things that he previously couldn’t, but contrariwise, he now cannot do things that as a deckhand he could, such as carry his effects to his new stateroom.

Sam, too, knows that the way the ship is supposed to work (no illicit alcohol) doesn’t match reality, and tells Max what happens when a previous Captain tried to forbid it. “Forces must balance, old son. For every market there is a supplier.”

When Max finally admits to Dr Hendrix that his service record is faked, Hendrix refuses to condemn him, although he clearly disapproves. “I am not going to pass judgement; you must do that yourself.” This is probably as good a summary as you can find of Heinlein’s slightly contradictory attitude, which is that ultimately your own self-respect must be your motivating force, and you must do your best to do the right thing.

It’s become my favorite juvenile. Great blog. Thank you!

Growing up, I was into sci fi AND into survival in the woods stories. So of course Tunnel was my favorite then. I remember crying when the kids all left and Rod was alone. (Despite realizing as I grew older how that deh-fuh-nitely is how things would go down.)

But after spending a good portion of 80s, 90s on Navy submarines, I really love Starman the most. Sure, the computers are different. But who cares. People are pretty well portrayed and shipboard experiences. The joy of qualifying a watch station is very much a USN thing. As are the “under instruction” watches. Never go to sea without a hangover, was definitely something I heard, from my salty skipper, in San Diego. The social distance (even on a close ship) of officers and men (the Navy is still 18th century in some ways, in it’s culture…only at sea is a many truly free!) The navigator sweating bullets reminded me a lot of our navigator on piloting parties (subs are a hassle on the surface). And the QMC was like he had stepped right off of my submarine (any of them!)